Apollo Client Real World Performance on a Large Ecommerce Site

I work on a large Ecommerce site for a major grocery chain. The application is built using a few tools that have been popular in the front-end space for the last few years:

- React (w/ SSR via a Node.js app)

- Apollo Client

- React-Apollo Bindings

The intent of this post is to document the performance cliffs I've encountered using Apollo Client in a real application. The goal is not to discredit any of the hard work from the folks at Apollo the company.

How SSR in React Works

Before digging into the performance challenges with Apollo Client, let's go through a quick summary of how SSR works in a React application.

History

Until recently, React did not provide a first-class API to perform asynchronous operations during rendering while executing on the server-side1. This posed a challenge for 3rd party library authors that often wrote their APIs thinking of React's client-first model.

Some folks in the open-source world came up with the concept of "two-pass rendering" to try and address this (though this can be a misnomer2). The general idea is that you render the React app once to initiate async work, and when the async work is complete you render the React app a second time. On the second render, the React app can synchronously read from the cache that was populated in the first render.

This is a cool work-around, but it has real performance implications: you're doing a lot of expensive things many times.

Simple (Synchronous) SSR Render

The steps to successfully render a basic application with SSR are roughly:

- Load the app in Node.js, and render the root component of the app using

renderToStringorrenderToPipeableStream. - Flush the generated HTML down to the client

- Load React on the client, and call

hydrateRoot, which instructs React to basically rebuild the "Virtual DOM" in memory, and ensure the current markup in the DOM matches with what React expects.

This SSR setup will not work with Apollo Client and React-Apollo because they need to perform work async to gather data.

Apollo Client SSR (Asynchronous)

Apollo Client implements the "two-pass" rendering strategy. The way you do SSR, with Apollo Client:

- Load the app in Node.js, and kick off Apollo Client's data-fetching on the server by passing the root component of the app to Apollo's

getDataFromTree. getDataFromTreecalls React'srenderToString, and waits for the synchronous render to complete. This causes alluseQuerycalls in some components to kick-off their HTTP requests.getDataFromTreethen discards the results from React.- When HTTP calls are complete, Apollo Client populates its cache, and then calls

renderToStringagain. This time, the React tree will see results synchronously in the Apollo Cache, and React will keep rendering until it finds the next unresolveduseQuerycall. This kicks off the next round of HTTP requests.getDataFromTree, again, discards the results from React. - Noticed a pattern yet?

getDataFromTreewill continue to render your app from top to bottom, recursively, until it's discovered everyuseQueryin the component hierarchy. - Once Apollo Client's cache has been populated with results for all

useQuerycalls,getDataFromTreeis complete. - The eventual result of

getDataFromTreewill be markup that can be hydrated again on the client. - Flush the generated HTML down to the client, along with a script tag that includes a serialized copy of the Apollo Client cache

- Load React on the client, construct an Apollo Client instance with the results from the serialized cache, and call

hydrateRoot, which instructs React to basically rebuild the "Virtual DOM" in memory, and ensure the current markup in the DOM matches with what React expects. During this process, React-Apollo will read query results from the cache instead of going to the network again.

There's a comment in the implementation of getDataFromTree that acknowledges the render must start from the root:

// Always re-render from the rootElement, even though it might seem

// better to render the children of the component responsible for the

// promise, because it is not possible to reconstruct the full context

// of the original rendering (including all unknown context provider

// elements) for a subtree of the original component tree.How we use Apollo Client

My employer's usage of Apollo Client is pretty typical of what you'd see in most applications following Apollo's official documentation. Engineers divide their queries into multiple queries that are distributed amongst the appropriate components. This is the recommendation in Apollo's Best Practices in the official docs.

One of GraphQL's biggest advantages over a traditional REST API is its support for declarative data fetching. Each component can (and should) query exactly the fields it requires to render, with no superfluous data sent over the network.

If instead your root component executes a single, enormous query to obtain data for all of its children, it might query on behalf of components that aren't even rendered given the current state. This can result in a delayed response, and it drastically reduces the likelihood that the query's result can be reused by a server-side response cache.

In the large majority of cases, a query such as the following should be divided into multiple queries that are distributed among the appropriate components

My experience in Production over the last couple years has shown me that this is not good advice if you care about the performance of your app, both on the server and on the client.

Example

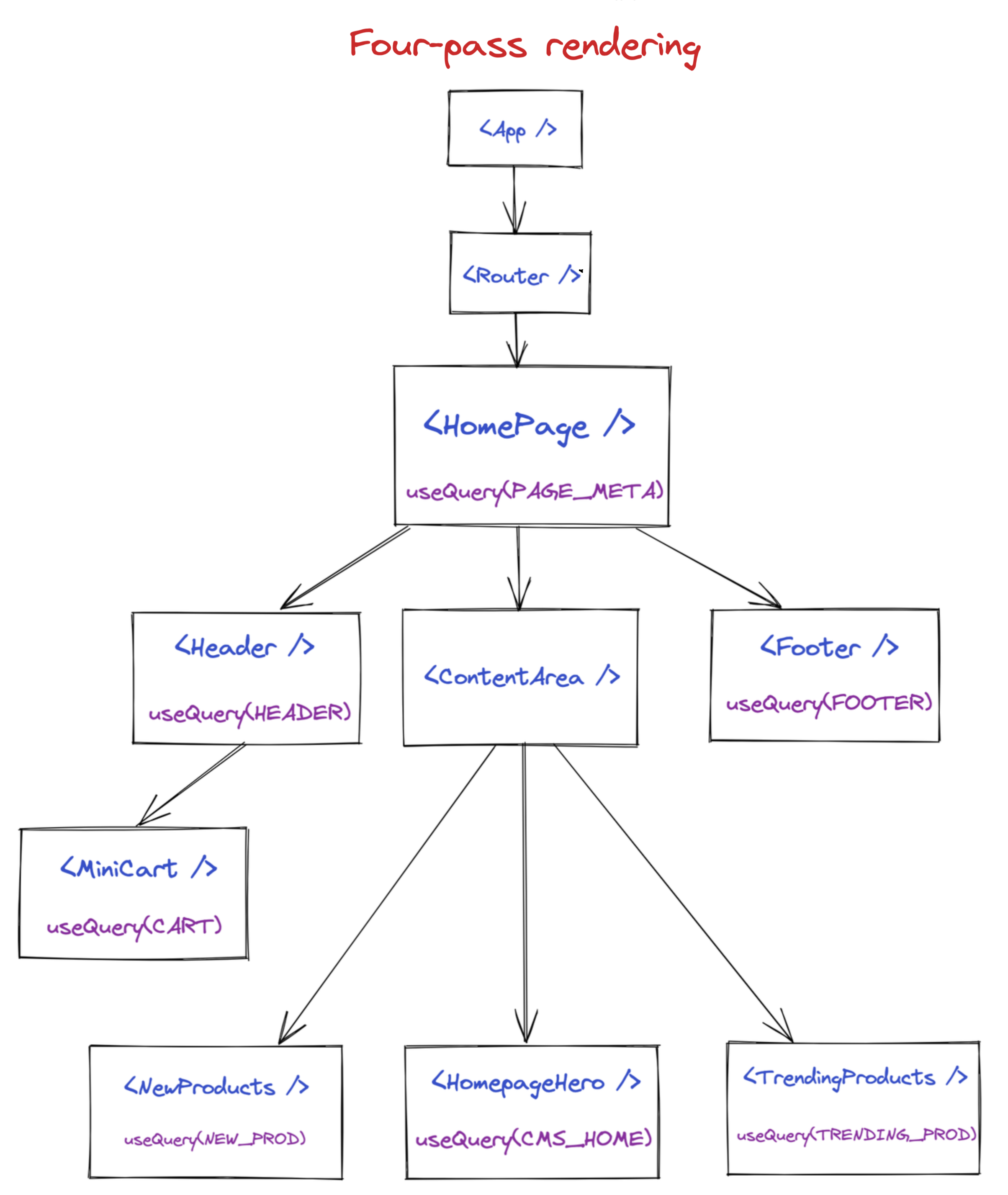

Below is a watered down example of a React component tree you may end up with when following Apollo's recommendation to distribute queries.

It may not be obvious, but this example requires calling React's renderToString 4 separate times on the server for a single request.

- First

renderToStringcall reaches<HomePage />. This component likely returns a loading state, and rendering stops until that fetch is complete. - Second

renderToStringis called. This time it renders the loading state for<Header />,<Footer />,<NewProducts />,<HomePageHero />, and<TrendingProducts />. Rendering stops until those fetches complete - Third

renderToStringis called. This time it renders the loading state for<MiniCart />. Rendering stops until that fetch completes - Fourth

renderToStringis called. This time every component found its data in the cache, and we can use the resulting markup from React.

Wait, how many HTTP Requests is that?

That's 7 separate HTTP requests to fetch data. While it occasionally makes sense to separate out HTTP requests for performance (fast vs slow queries, critical vs secondary content), this is a bit excessive, especially since a selling point of GraphQL is limiting the number of HTTP requests on the client (compared to REST).

Apollo offers one solution to this in the form of the BatchHttpLink. It works by operating in 10ms (configurable) windows. Every 10ms, it grabs the last queries its seen, and batches them into 1 HTTP request.

This means that, for many requests, you're introducing an artificial delay on the client! If the main thread is chomping through a large number of tasks when the end of the 10ms window is hit, the delay can be much longer.

Data!

Bundle Impact

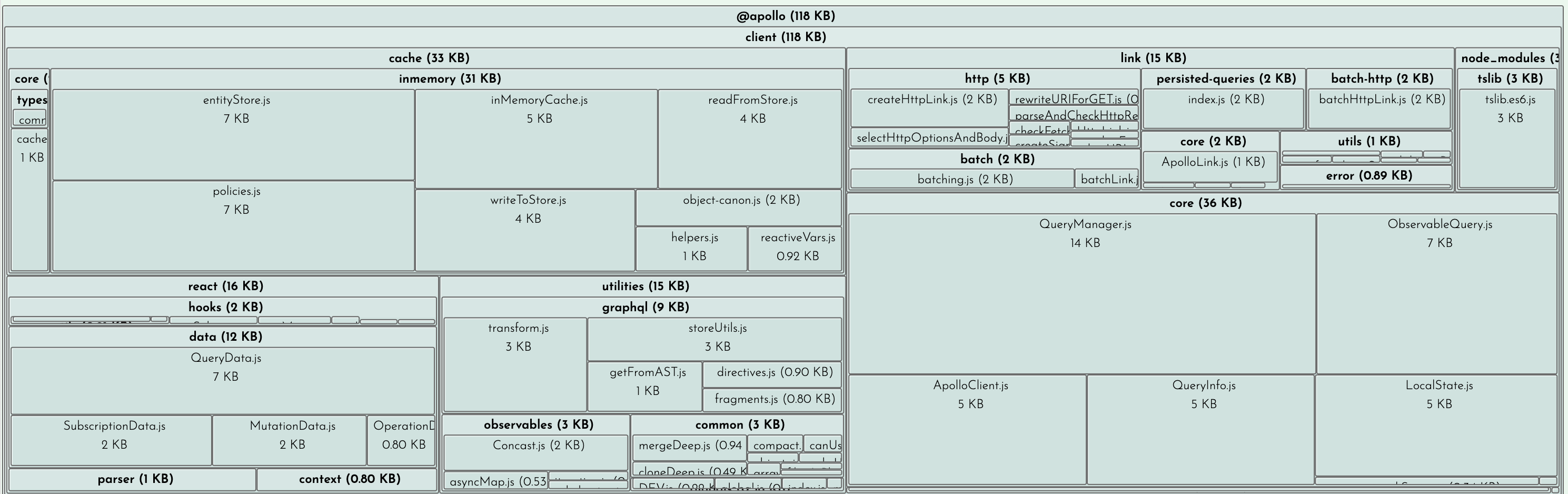

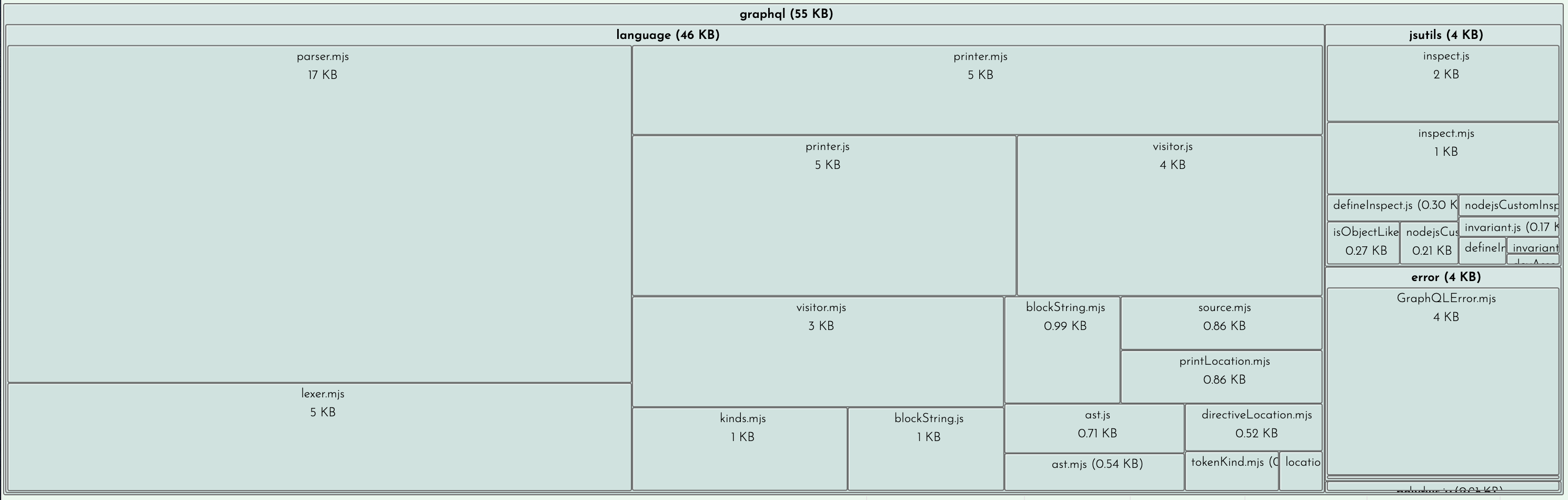

Note: These numbers are before minification. You probably shouldn't expect minification to drastically improve the performance of your app, though.

This data was extracted with the SourceMap Explorer in Bundle Buddy.

118 KB from the @apollo/client package and its dependencies

55 KB from the graphql npm package (required by Apollo Client)

SSR Performance

All the traces below were captured in Node.js v16.12.0 on a 2019 MacBook Pro i9.

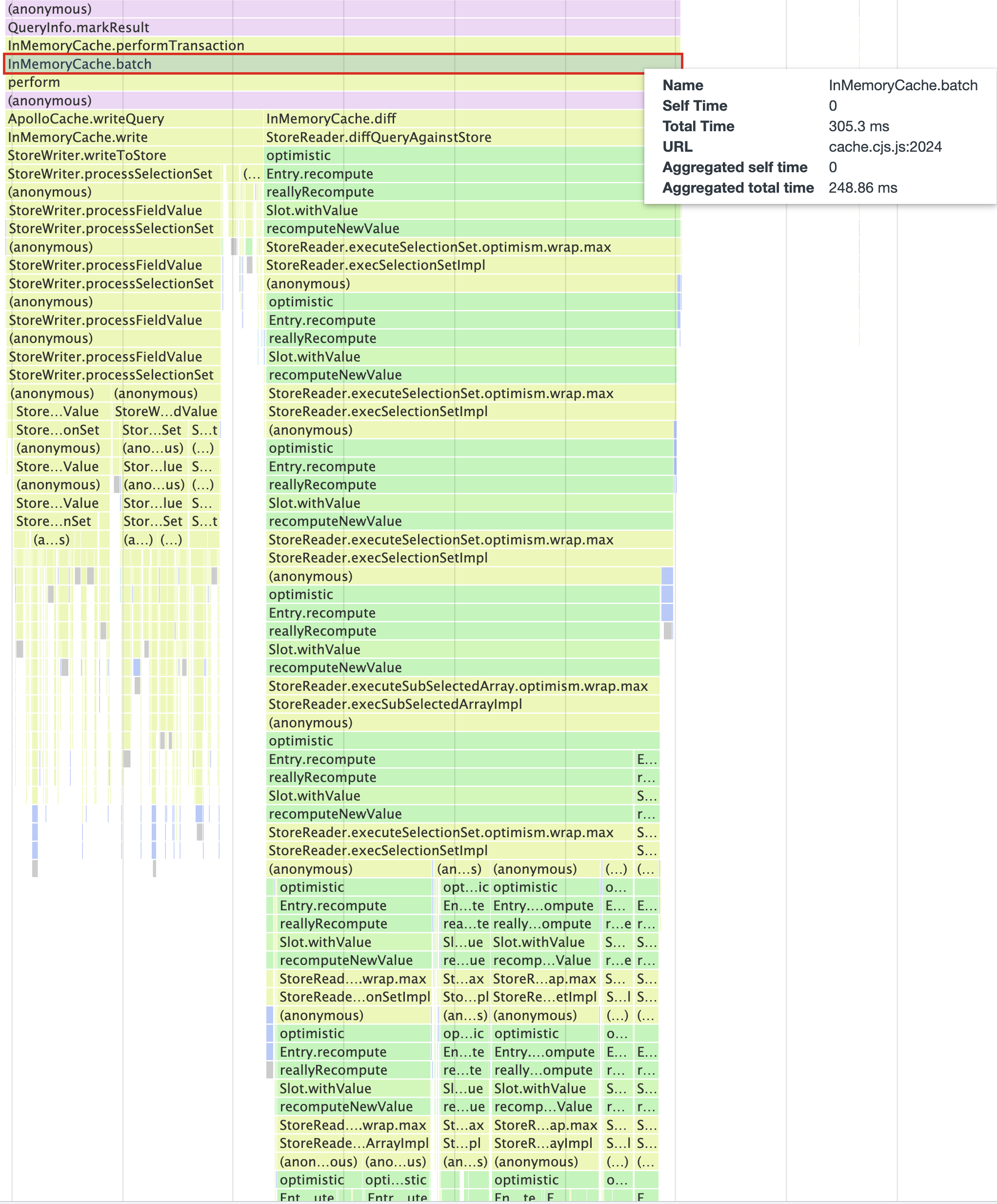

Cache Write Costs

Similar to the client-side, writing to the cache is extremely expensive. For a single write to the cache during one of our renders (remember we have to render many times), we block the main thread for over 300ms:

Hydration/Client-Side Performance

All the traces below were captured in Chrome 107.0.5304.105 on a newly purchased 2022 Moto G Power device running Android 11. According to @slightlyoff, this device is representative of a mid-tier Android device in 2022.

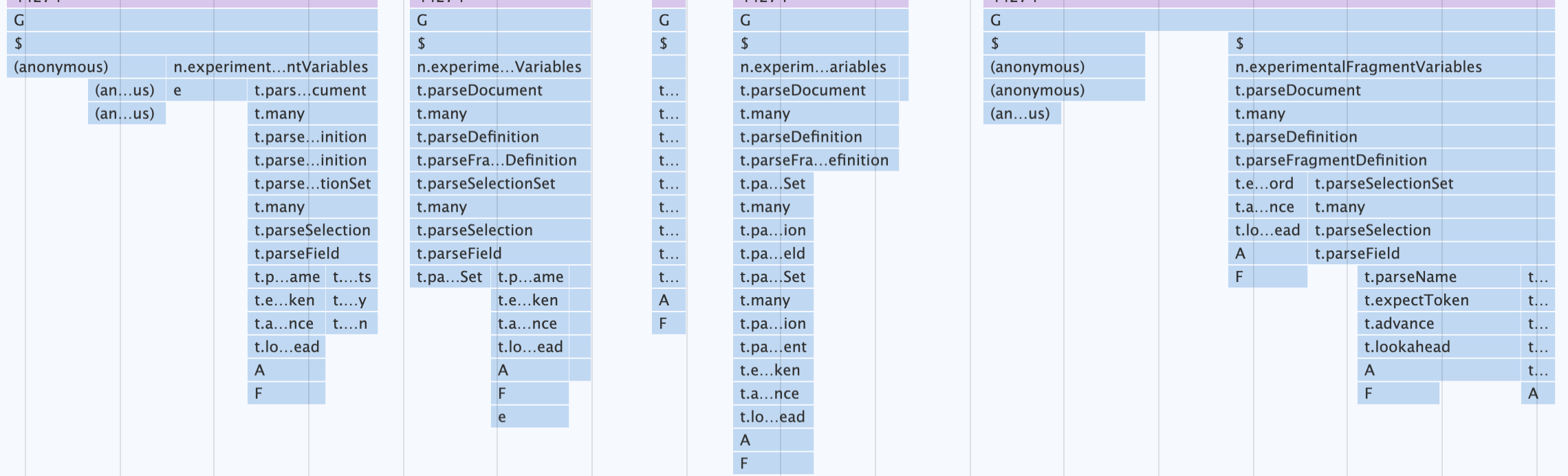

Query Parsing Costs

Although you author queries as strings, Apollo Client requires each query to be parsed so it can be analyzed on the client-side. This is done using the gql tagged template literal provided by the graphql-tag library.

Example

import { gql, useQuery } from "@apollo/client";

const QUERY = gql`

query {

currentUser {

id

}

}

`;

export default function UserIDComponent() {

const { data } = useQuery(QUERY);

return (

<div>

{data ? data.currentUser.id : "Loading"}

</div>

);

}In this example, note that the usage of the gql tag is in the "top-level" of this file (module). This means the moment this file is imported on the client-side, the main thread will be blocked running GraphQL's parser over this query.

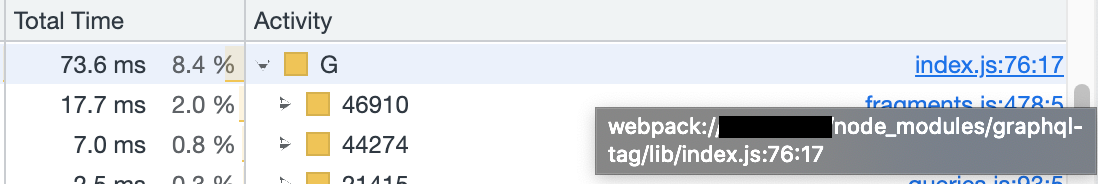

To render our Home Page, my device spent ~73ms running all the queries in the bundle before React even had a chance to start hydrating the app.

Total time spent by the gql tag prior to React hydration

Zooming in shows each file going through GraphQL's recursive descent parser

Query Execution Costs

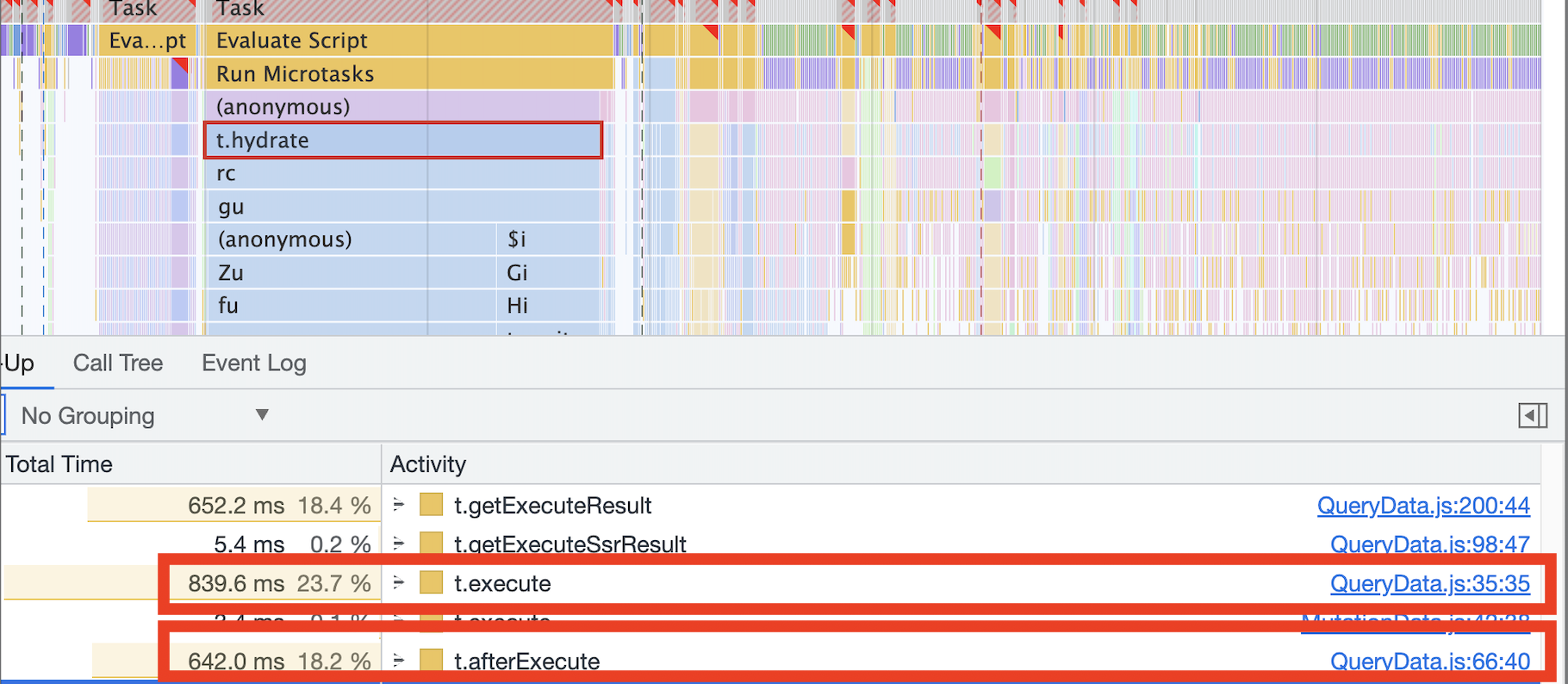

The cost of executing queries is, by a wide margin, the most expensive thing Apollo does on the client-side. During React hydration, it easily blocked the main thread for > 1s on my device. As far as I can tell, most of this slowness can be attributed to the InMemoryCache.

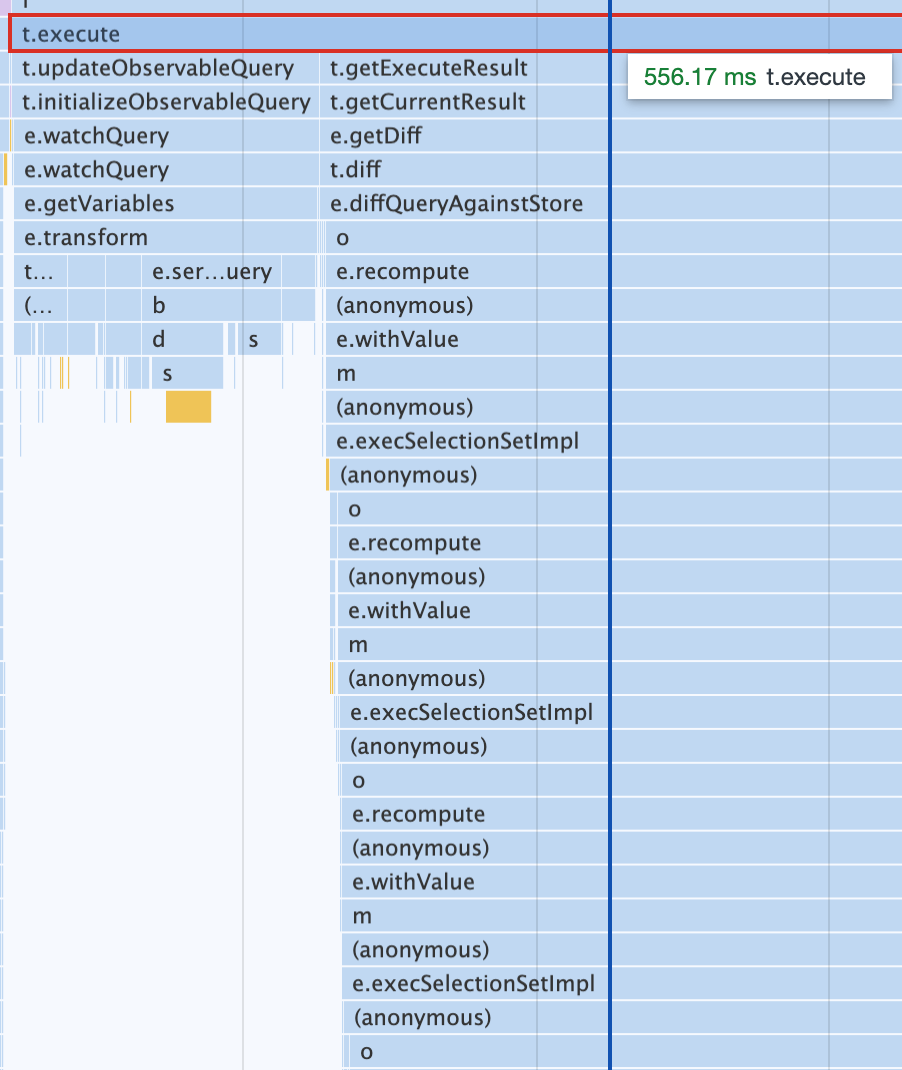

Apollo's React integration with useQuery works in 2 phases:

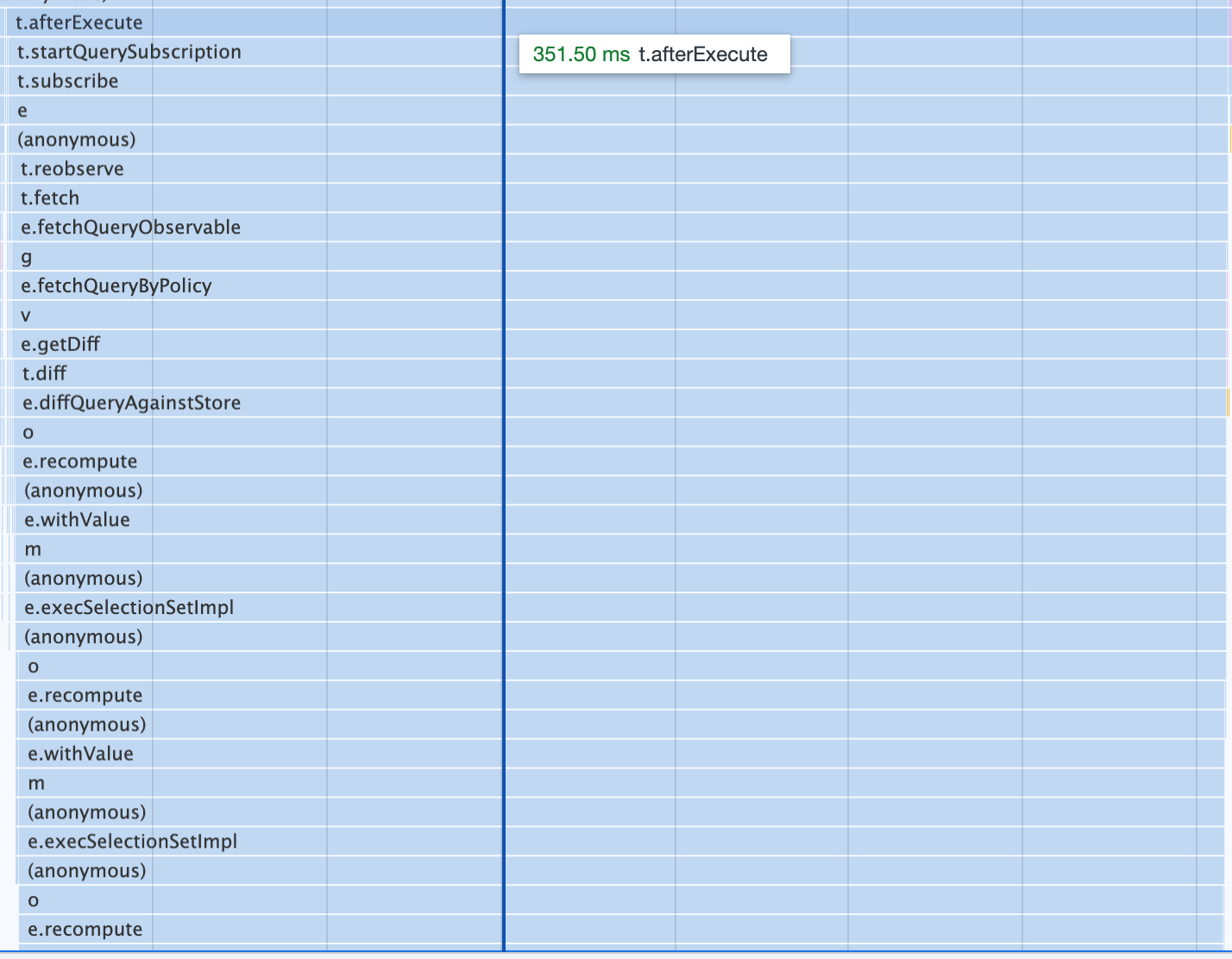

useQuerycallsQueryData.prototype.execute, which executes immediately during a components' renderuseQuerycallsQueryData.prototype.afterExecutein auseEffect, meaning it runs immediately after React has updated the DOM with any changes from the last render.

For the Home Page in our application, both of these phases can block the main thread for several hundred milliseconds, even though we already have a cached result in memory and don't need to touch the network. For many devices, it would be cheaper if we ignored the cache and fetched a fresh result from the network.

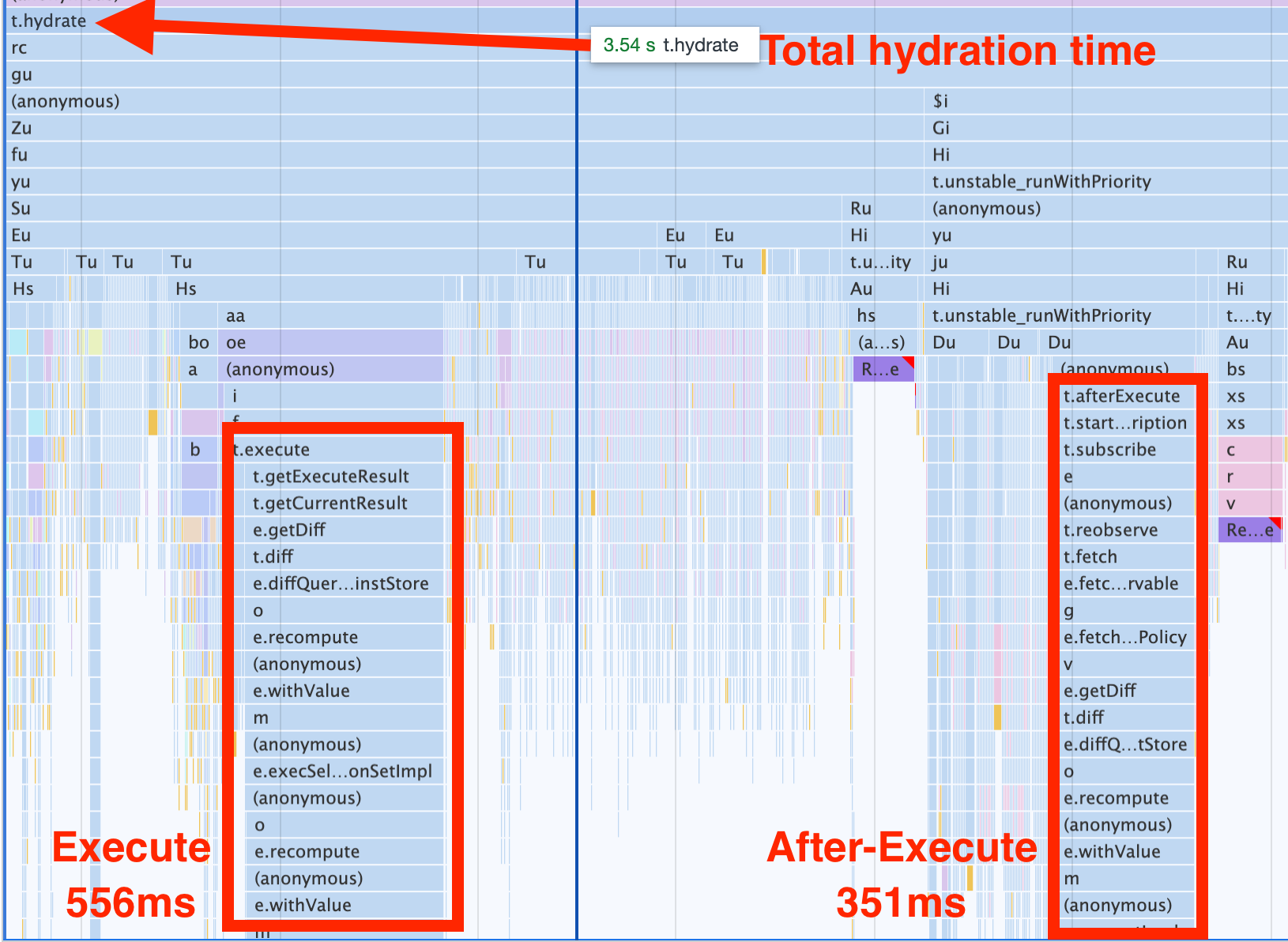

Execute phase blocking for 556ms

After-Execute phase blocking for 351ms

These costs are so expensive compared to other libraries that they stand out clearly when looking at the total cost of React's hydration

Full Hydration

Total Hydration Costs of Execute + After Execute (~1.6s)

It's important to note that you pay this cost for every component on the page using the useQuery hook. In this example, I'm only showing the costs for a single component. If you display 50 products on a page, and each of your <Product /> components has its own useQuery call, you're running both these phases 50 times.

I should note that not every execute and afterExecute phase is this expensive (although the cumulative costs still aren't great for large component trees). The challenge is that it's not remotely clear what makes these phases so expensive, or what the recommendations would be to remedy.

Footnotes

-

React now supports this directly via

renderToPipeableStreamon the server andReact.Suspense↩ -

Apollo has no limit on the number of "passes" it will perform. This can be observed by looking at the recursive calls to

processingetDataFromTree↩